Americans living today have never seen a former president seek a return to the Oval Office. The two-term limit is one reason for that. The limit first applied to President Eisenhower, and it means that two-term presidents such as Eisenhower, Reagan, Clinton, or Obama could not attempt a comeback even if they wanted to. The closest to a comeback we have seen in recent history are proxy returns through family members, such as George W. Bush avenging his father’s loss, or Hillary Clinton seek a Clinton restoration.

News reports claim that President Donald Trump may consider a comeback bid for the White House in 2024. Under the terms of the 22nd Amendment, a person may serve two four-year terms as president.

Trump, who was elected in 2016, has not conceded defeat in 2020, but if he does in fact lose when the electoral college votes on December 14, he would be eligible to run again in 2024. If elected in that year, he would exhaust his two terms and could not run again.

There has also been speculation about another member of the Trump family seeking a “proxy comeback” through a White House bid. A 2024 candidacy by President Trump himself, however, would not be without precedent in American history:

Martin Van Buren, 1844 and 1848

The first serious comeback bid by a former president was launched by Martin Van Buren in 1848. Van Buren was a political animal – one of the nation’s first “operatives” – who helped Andrew Jackson found the Democratic Party. He served Jackson as Secretary of State and as Vice President, and then followed Jackson into the White House in 1836. Four years later, amidst a recession, he lost reelection to William Henry Harrison.

Van Buren attempted a comeback in 1844, seeking the nomination at the Democratic National Convention, but his candidacy was damaged by his opposition to the annexation of Texas. At that time, the Democratic Party required two-thirds of the delegates to secure a nomination (a rule designed to require regional balance), and neither Van Buren nor his chief rival, U.S. Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan, could reach that threshold. Finally, the convention broke the deadlock by nominating Governor James K. Polk of Tennessee, a compromise candidate and the first “dark horse” to be nominated for president.

By 1848, Van Buren had become increasingly alienated from the Democratic Party. He opposed President Polk’s annexation of Texas and his entry into war with Mexico. He also came to hold strong anti-slavery views. A new anti-slavery third party, the “Free Soil Party,” nominated Van Buren for President and Charles Francis Adams (son of John Quincy Adams) for Vice President.

Ultimately the Whig ticket of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore prevailed against the Democratic nominee, Van Buren’s 1844 rival Lewis Cass. Van Buren’s Free Soil ticket did not win any electoral votes, but he won approximately 10 percent of the popular vote and laid the groundwork for the founding of the Republican Party.

Millard Fillmore, 1856

Fillmore was never elected president. He was Zachary Taylor’s running mate on the Whig ticket in 1848. Taylor died in 1850 and Fillmore succeeded to the office. Taylor’s death happened at a pivotal time; President Fillmore signed the Compromise of 1850, which Taylor likely would not have supported. The compromise may have delayed the Civil War by ten years, but included aspects such as the Fugitive Slave Act, which was unpopular in northern states. For that reason, when Fillmore sought his own term in 1852, he lost the Whig Party’s nomination to General Winfield Scott, who in turn lost the general election to Democrat Franklin Pierce.

By 1856, the Whig Party had splintered. Many northern Whigs had joined with Free Soilers, and some northern Democrats, to form a new Republican Party, which nominated U.S. Senator John C. Fremont for president. The Democrats, still seeking to avoid the slavery question, nominated James Buchanan, who had been overseas on diplomatic missions and had avoided taking sides on issues such as the Compromise of 1850.

Fillmore accepted the nomination of the “American Party,” commonly known as the “Know Nothing Party,” which was made up of the remainder of the Whigs and with nativist elements that were opposed to immigration and to the Freemasons. Fillmore won 21.5% of the popular vote, but carried only a single state – Maryland – as the presidency went to Buchanan.

Ulysses S. Grant, 1880

Grant, the Union general and Civil War hero, served two terms as president from 1869-77. He did not seek reelection in 1876, giving way to fellow Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. President Hayes declined a second term, and Grant entered the 1880 Republican National Convention as the front-runner for the nomination. Grant had the support of New York party boss Roscoe Conkling; his main rivals were U.S. Senator James G. Blaine of Maine and John S. Sherman of Ohio, the secretary of the treasury. Grant led the early balloting but could not achieve a majority, and the Blaine and Sherman forces eventually shifted their support to Congressman James A. Garfield of Ohio, who won the nomination and was elected the 20th President.

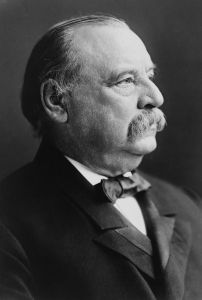

Grover Cleveland, 1892

Grover Cleveland is the only former president to successfully regain the office. In fact, he is probably best known to school children as “the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms.”

Cleveland, the governor of New York and a former mayor of Buffalo, was first elected in 1884. A Democrat, Cleveland was seen as an anti-corruption reformer, and he narrowly prevailed against James G. Blaine, a Maine politician who had served as Secretary of State, U.S. Senator, and Speaker of the House.

Cleveland lost reelection in 1888, though, against U.S. Senator Benjamin Harrison of Indiana. Cleveland actually won the popular vote, 48.6% to 47.8%, but lost the electoral college 233-168. Harrison won Cleveland’s home state of New York, which was decisive, and the election turned primarily on the issue of tariffs. (Cleveland supporting a low tariff, and Harrison a protectionist tariff).

Cleveland remained popular and Democrats supported him again in 1892. The tariff once again dominated, although a new Populist Party, pushing the free coinage of silver, drew support from both major parties. Cleveland won the rematch against Harrison, with Populist James B. Weaver winning electoral votes in six western states.

Unfortunately for Cleveland, his reelection was followed by the calamitous Panic of 1893. Given the weakened economy, Cleveland did not seek reelection in 1896, and Democrats turned away from his policies, nominating Populist William Jennings Bryan for president.

Theodore Roosevelt, 1912

Roosevelt, a hero of the Spanish-American War and newly-elected Governor of New York, was nominated for Vice President on a ticket with President William McKinley in 1900. The move was famously orchestrated by party bosses who wanted Roosevelt out of the governor’s office. That backfired when, in September 1901, McKinley died after being shot while visiting Buffalo, New York.

Roosevelt completed McKinley’s term, and then was easily reelected in 1904. In observance of the traditional two-term limit, he announced that he would not run again in 1908, choosing to consider the 3 1/2 years he served of McKinley’s term as his “first term.” He quickly came to regret the decision, though, as his preferred successor, William Howard Taft, failed to pursue Roosevelt’s progressive policies with the vigor he expected.

Disappointed with Taft, Roosevelt launched a bid to retake the White House in 1912, “clarifying” that he had only meant to limit himself to two consecutive terms. His attempt to win the Republican nomination failed, as Taft’s forces controlled the nominating convention, so Roosevelt bolted the party, creating the Progressive “Bull Moose” Party in competition against Taft and the Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson. Although all three candidates claimed to be “progressives,” the effect of Roosevelt’s candidacy was to split the Republican vote, delivering the White House to Wilson. (Wilson won only 41.8% of the popular vote, but won 435 of 531 electoral votes.)

Roosevelt continued to be an active political figure following his 1912 loss. In 1916, he endorsed Republican nominee Charles Evans Hughes, reuniting the Republican and Progressive parties, but Hughes narrowly lost to President Wilson. Roosevelt was seen as the front-runner for the Republican nomination in 1920, but he died in suddenly in 1919, aged only 58.

Since 1912

No former president has launched a serious comeback bid since Roosevelt in 1912. In 1932, some Republicans floated the idea of a Calvin Coolidge comeback to replace President Hoover, who was heading for a massive defeat to Franklin Roosevelt. Coolidge, though, had no interest. Hoover, in turn, was floated as a potential nominee at the next few Republican conventions, but never pursued the nomination or gained any traction as a candidate.

Following President Ford’s defeat in 1976, his supporters urged him to consider a comeback in 1980, hoping he could be a moderate alternative to Ronald Reagan. Ford declined, and his backers supported other candidates including George H.W. Bush.