The last week of the legislative session always focuses on finalizing the state budget. As the news reports on the negotiations and posturing, I have had a few people ask me if the legislature has ever failed to pass a general appropriations act.

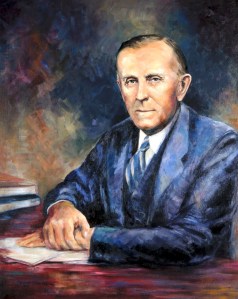

The only time I am aware of is the 1927 legislative session. That was Governor William J. Bulow’s first year in office. He was the state’s first Democratic governor, serving alongside a strongly Republican legislature.

I had the opportunity a couple of years ago to edit Bulow’s unpublished autobiography, excerpts of which were published by South Dakota History in its Spring 2021 edition. Below is a selection from Bulow’s memoirs, in which he describes the events that led to his veto of the general appropriations act in 1927:

I had made my campaign stressing a balanced budget. That state expenses must be kept within revenue income. I said that if we continued to expand each year in excess of revenue income, and without giving any attention to revenue income. we were headed for bankruptcy. The Republican stewardship had been wrong and there needed to be a change. I told people that when I came to the state as a young man, the state then had no bonded indebtedness. It was then the boast of the people of South Dakota that the state had the highest per capita income, and the lowest per capita tax, of any state in the union, but under the Republican stewardship over the years, we now had a bonded debt of over sixty-five million dollars, and we were fast approaching the record of becoming the highest per capita debt of any state in the union. I said that this thing had to stop – this reckless spending without regard to revenue income had to be halted. [This debt was due to the failure of the Rural Credit program, a state ag lending program created by Governor Norbeck, whereby the state borrowed money at a low rate and loaned it out to farmers. The program became insolvent during the farm crisis of the early 1920s, and it took the state until the 1950s to pay off the debt.]

I put great stress on this in my message to the legislature and gave the members of that body to understand that I would not approve appropriations in excess of revenue income. When the annual appropriation bill came to me for approval it reflected the same old story. From the best information I could get, the legislature had appropriated more than a million dollars in excess of the possible revenue income. I promptly vetoed the measure. In a message I gave the legislature two alternatives: they must either cut down the appropriations to within the revenue, or they must provide more revenues. The House promptly overrode my veto and passed the bill, but its passage was blocked in the Senate. There were sixteen Democratic senators in the Senate who stayed by me, plus one Republican, Senator Hicks from Lincoln County who joined with the Democrats, and the appropriation bill went down to defeat.

This made the Republican legislative members awfully mad, and they decided not to pass any other appropriation bill. They had ample time in which to do so before the sixty-day limitation of the session expired, but they decided not to do so. They sent word to me and wanted to know how I was going to collect my salary and how I was going to run the governor’s office after the first day of July when all appropriations expired and there would be no money to pay me. I sent word back that I did not need any money to run the governor’s office; that all I needed to run that office was plenty of chewing tobacco, and a few good Democrats had agreed to supply that. I was going to get along all right, but I was wondering what all the Republican officeholders were going to after July 1st.

Immediately after adjournment of the legislature, the Republican leadership brought an original action in the Supreme Court against me, in which they contended that a governor has no power to veto a general appropriation bill. All the judges of the supreme court were Republican, but they were all men of the highest integrity and I was perfectly willing to submit the case to them and abide by their judgment.

In as much as the salaries of the judges were involved in the appropriation bill which I had vetoed, the members of the court felt that in good ethics, they could not sit as judges in the case. Under provisions of law they could, in such cases, select a special court from among the lawyers of the state to sit as special judges. This was done. Five prominent lawyers were selected from the membership of the state bar. Three were Republicans and two were Democrats, and they sat as judges and tried the case.

The case was hotly-contested and well-tried. The judges reached a unanimous decision sustaining the governor’s veto. At the end of the fiscal year, June 30th, all unexpended appropriations would revert back to the general fund, and after that there would be no money for any of the state activities. It was necessary to call a special session of the legislature to provide for funds to carry on the business of the state after July 1st.

I waited until well into June before making the call. When the legislature reassembled, everyone was in better humor. The legislative members had visited with “the boys back home” and had discovered that the “boys back home” were not particularly mad at the governor and were in favor of cutting down state expenses. We had no difficulty in getting together on a new appropriation bill and fixed it so that all the boys on state payroll had a little money to spend in celebrating the 4th of July.

Bob Mercer, writing a “Capitol Notebook” column in the Black Hills Pioneer on March 29, 2010 about end-of-session budget jockeying between Governor Mike Rounds and legislators, offered his own version of the Bulow budget standoff:

In 1927, the Legislature had to return in a special session to deal with a similar but stranger situation. The state’s first Democratic governor refused to sign the budget bill, and he had good reason. There wasn’t enough money to cover all of the spending approved by the Republican-majority Legislature.

The action by Gov. W. J. Bulow was especially odd because he didn’t actually veto the budget bill. He simply sent it back to the Legislature, along with a strong message that never mentioned the word “veto.”

The Legislature had presented the General Appropriations Bill, SB 113, to the governor on Feb. 24, 1927. A few days later, on Feb. 28, the governor handed it back. He wrote:

“This is a business proposition, and we cannot continue to spend in excess of our revenue income. It is necessary for this Legislature to do one of two things: either reduce the amount of total appropriations within the revenue income, or provide the necessary revenue to meet the appropriation expenditure.”

The Senate reconsidered the bill on March 3 as a veto override. The first time through the Senate it had passed 44-1. But the second time, the stakes were much higher. The vote was 28 yes and 17 no. Failing to get a two-thirds override, the bill was lost. The next day, the Legislature finished the 1927 session and went home without a state budget. The two chairmen of the appropriations committees had a backup plan.

They went to the state Supreme Court in an attempt to get the budget bill declared as law. They filed suit against Secretary of State Gladys Pyle, seeking to force her to furnish them a certified copy of the bill as though it was law.

Pyle refused to furnish it because she was in doubt that the bill had become law after Bulow had returned the bill to the Senate, neither signed or vetoed. The characters at the center of this precedent-setting political and legal struggle came from throughout South Dakota.

Sen. [Carroll D.] Erskine was a Republican and the pastor of the First Presbyterian church in Sturgis since 1906. He was first elected to the Senate in 1920. Rep. [George B.] Otto was a Republican from Clark who was the state’s attorney in Clark County and was in private practice there. He was first elected to the House in 1920.

Secretary of State Gladys Pyle had been the first woman to serve in the Legislature. She was a member of the House from Beadle County, elected in 1922 and 1924, and had served with Erskine and Otto. She coincidentally served as assistant secretary of state from 1923 to 1927, when she took office as secretary of state.

The state attorney general representing her was Buell F. Jones of Britton, a Republican. He was born in Spain, South Dakota, and was Marshall County state’s attorney before his election in 1922. But because of the unique circumstances, Pyle and Jones essentially were the surrogates on behalf of the Democratic governor.

Bulow was born at Moscow, Ohio in 1869. He held a law degree from the University of Michigan and began practicing at Beresford in 1894. At various points he was a county judge, mayor, city attorney and a state senator. He was elected governor in 1926, even though the state’s two senators and three representatives were all Republicans.

The two legislators, represented by the Pierre law firm Fuller and Robinson, filed an original proceeding in the state Supreme Court. But the court’s judges decided they shouldn’t hear the case, nor should any of the circuit judges, because the state’s judicial system’s funding was in the budget bill.

Instead five lawyers were selected to serve as Supreme Court judges. They were William G. Rice of Deadwood, James Brown of Chamberlain, Philo Hall of Brookings, F. D. Wicks of Scotland and Emmett C. Ryan of Aberdeen, with Brown acting as presiding judge.

They delivered their unanimous opinion on April 21, little more than a month after the legislative session ended. They ruled in favor of Secretary of State Pyle and Gov. Bulow, declaring that “the Governor is clothed with full power to veto the General Appropriation Bill as a whole” or to veto any item or items in the bill.

Now the budget passed by the Legislature was truly dead. Legislators returned for a wide-ranging special session June 22, 1927, through Friday, July 1, and one of the bills they passed was a new general appropriations act.

Then Gov. Bulow took out his veto pen again. On July 9, he approved the new bill but made line-item vetoes of specific amounts in a variety of agencies and departments. He said the totals appropriated by the Legislature exceeded the revenue available and the vetoed items could be stricken “without injury to any of the necessary state activities.”

Bulow’s memoirs glosses over the his failure to use the word “veto” – his message stated that “I cannot approve this measure,” making his intent clear, and the Legislature treated it as a veto, immediately attempting an override. A review of Erskine v. Pyle, 51 SD 262 (1927), reveals that the legal theory espoused by Senator Erskine and Representative Otto was that the constitution’s specific grant to the governor of a line-item veto meant that this was the only was to veto a general appropriations act; that is, the governor would have to line-item veto every line to veto an entire budget. The Supreme Court rejected that view, finding that the two veto provisions were alternatives: the governor can veto any bill, including an appropriations bill, in its entirety, but can also use a line-item veto to strike specific provisions in appropriations bills.